Disclaimer: Today’s post will be pretty different from my usual stuff. The first part will be reflective. I’ll give some context for my title. In the second half, I’ll add some analysis and, specifically, bring in ethical perspectives on the topic. This is also very similar to an essay I wrote in my post-grad, but it is reworked, way less academic, shorter and more reflective. Let me know if you guys like this kind of content!

Background

So, I decided to give up the “clock app” for Lent, because I knew I had a problem: I was genuinely addicted to scrolling. It’s something I’d long accepted about myself over the past four years, as every time I had exams and coursework in university, I’d periodically delete the app to try and revive my attention span.

Last year, specifically, I had an interesting epiphany! During my MSc, I’d spend hours in the library and then every few hours, I’d find myself outside the post-graduate room just scrolling on a certain short-form video app as a “break”. I then realised that I would return to my desk from my “breaks” exhausted, and it dawned on me that what I was doing was counter productive: I was trying to take a break, but in that break engaging with something visually and still in some form of “deep thought” and I would extend my time on the app because every time I scrolled, there was always something more interesting, more relevant, more “me”. It then dawned on me that if I spent the majority of my time working, and when I wasn’t working, I would spend pockets of free time (e.g. lunch break or on the bus) online. I had to ask myself: when was my brain actually resting? and how was this impacting my work?

So, in the lead-up to the exam season, I decided to delete the app and test out how this would affect my energy levels and the quality of my work. No surprise; I genuinely had the time of my life studying for those exams and writing the coursework. Hours and hours would go by, and there I was just writing/editing…I’d head home from the library, maybe listen to a podcast or music or be still with my thoughts and get home excited to write more and, more importantly, ready to. For the first time in a few years, I remember just thinking, “Wow, my brain doesn’t feel like it’s overheating! I ACTUALLY get to rest!” In that moment last year, it truly dawned on me the adverse impact it was having on me. After this realisation, I continued the trend: when I had important deadlines, I would simply just go offline.

However, the issue is: this only worked for me during my time at university, as there was a distinct separation between term time and holiday time, but once I graduated, I slipped back into my old patterns. Enter: Lent! A 40-day period of reflection for Christians, the perfect time to give up something significant, to sacrifice and to step into my faith. This year, I decided to give up the original short-form video content app. I’m so glad that this is what I chose to give up. On the one hand, because it was meaningful to me as I genuinely enjoyed using the app. Aside from the time-consuming aspect of it, I enjoyed my algorithm, my saved videos, and the ability to explore niche topics I’m interested in and creators I follow. That’s why I spent a lot of time there. So, giving it up does embody the spirit of Lent because it is meant to be a period of sacrifice. But, another reason I gave it up was because I genuinely am against the design and algorithm from an ethical perspective.

Whilst doing my MSc, I decided to take a course called “The Ethics of Data and AI” and it was perfect. Yes, aspects of it were technical, and I did have a teary-eyed moment with my tutor about the technicalities, but in no way do I regret taking that class. I already had somewhat of an interest in the ethics of technology due to some COVID reflections on the creation of a “digital world” and the impact this has on connections, but this deepened my interest in this area and introduced me more to debates in a highly relevant area: AI! But that’s beside the point. In this class, I learnt about AI and the future of work, algorithmic fairness, the notion of intelligence, and in my favourite week, we learnt about the concept of “digital nudges”. Today’s piece is about this: digital nudging, my ethical objections to it and how ultimately, if you find yourself constantly scrolling, it’s not your fault.

Examining this from an ethical perspective

What are digital nudges?

A nudge is 'any element of the choice environment that consistently influences people's actions without restricting their options or substantially changing their economic incentives' (Veliz, 2021). This essentially means changing the choice environment to make certain actions more likely than others. For example, if I wanted to nudge my dog to go on a walk, I might put a treat right next to his leash. Digital nudging specifically is when nudges are applied via digital means, which looks like using tactics like predictive analytics to anticipate a user’s decisions or seizing a user’s attention through addictive interfaces (Veliz, 2021). One great example of this: the infinite scroll on TikTok, which also happens to be my very issue with the app.

Why are you constantly scrolling?

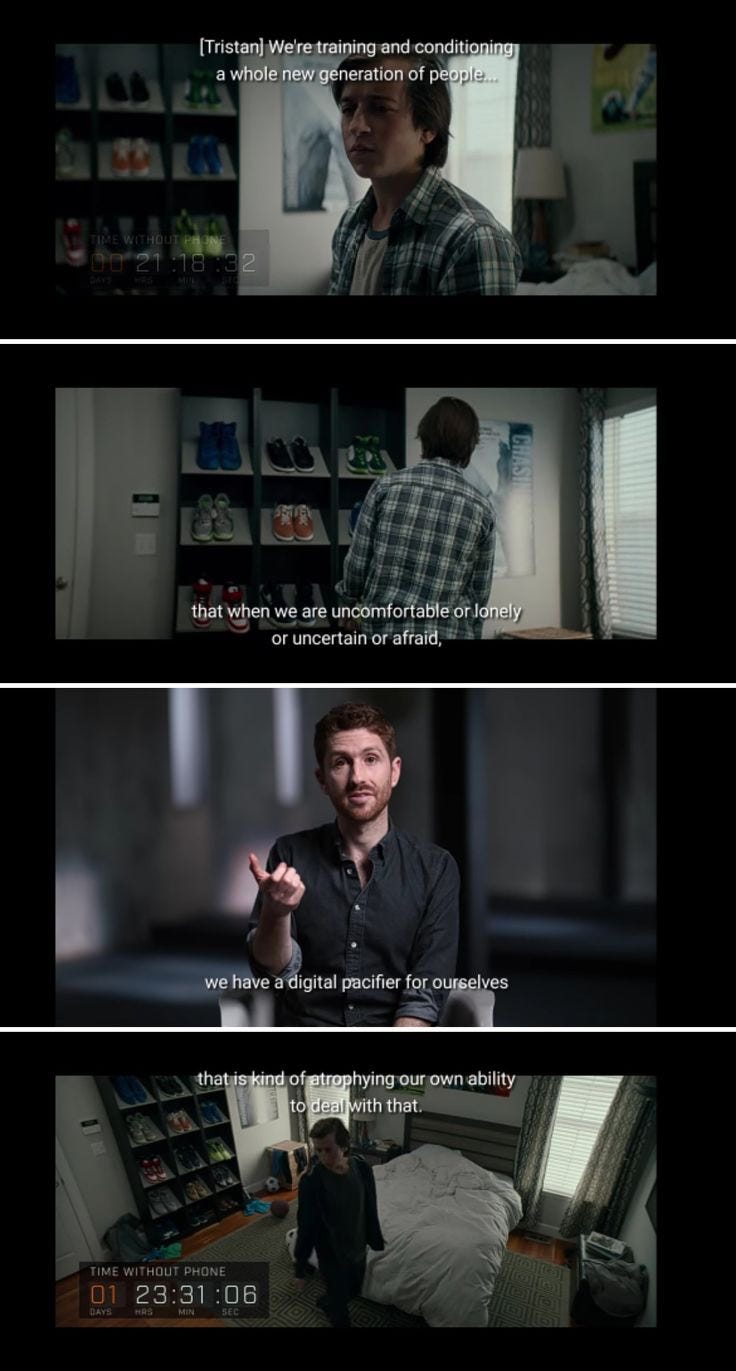

At first, when I found myself having an issue with doomscrolling, I labelled it as a self-discipline issue in my mind: I just needed to get a grip and delete the app or just limit my usage significantly, and the fact that I couldn’t do that was my fault. But, when I took this course and learnt about digital nudging and started researching the area of social media addiction and read the paper “Ethics of the Attention Economy: The Problem of Social Media Addiction” by Vikram R. Bhargava and Manuel Velasquez, I realised that this wasn’t a personal problem, this was a design issue. This is because social media apps such as TikTok use persuasive technology, which not only influences behaviour but also gives these apps the potential to become addictive as they distort how the brain functions by manipulating its stimulation-seeking tendencies. For instance, the erosion of natural stopping cues which alter the choice architecture by increasing the likelihood of prolonged app usage. This can specifically be seen through the infinite scroll, which eliminates natural stopping cues. Additionally, using positive intermittent reinforcement techniques through features like the ‘automatic refresh” creates uncertainty about the timing and nature of rewards to encourage continual engagement. Ex-designer at Google, Tristan Harris, has explained the way this persuasive technology works as he states that linking actions to variable rewards, akin to a 'slot machine effect,' maximises addictiveness and profitability, a strategy designers are often aiming to replicate.

Image credits: Social Dilenma, Netflix

What’s the problem with this?

This is particularly harmful due to the various physical and mental health consequences associated with social media addiction and excessive use. Prolonged social media use, which has been facilitated by these digital nudges, correlates with negative health implications such as increased rates of mental health disorders like depression and anxiety, elevated recreational drug use, and the development of unhealthy eating and exercise habits.

Additionally, another harmful aspect is the way it harms one’s ability to live a dignified life. The concept of a dignified life is widely discussed in philosophy; one of the most popular theories can be found in the work of Martha Nussbaum through her “capabilities” approach. Nussbaum outlines specific human capabilities which she believes are essential for living a life of dignity and ultimately, will allow individuals to pursue whatever their conception of “good is”. One example of a 'capability' is "senses, imagination, and thought.” This covers the ability to imagine, reason and produce self-expressive works. Excessive social media seriously impacts this. For instance, tactics like "hijacking human attention" through features such as infinite scroll and auto play have been proven to adversely affect critical thinking, rationality, and meaningful social interactions. It is problematic for digital nudges to encourage behaviour that harms individuals. Such practices arguably demonstrate a lack of respect for users as an end in themselves whose worth, desires and interests deserve to be considered. This commodification of humans and viewing individuals as products as opposed to an ends in themselves is ethically questionable as it goes against fundamental ideas of respect and the intrinsic worth of humans.

Due to the inherent nature of nudges, it may not seem like the case. As, by definition, nudges do not explicitly restrict choices or offer economic incentives. One could even argue that people still have the 'freedom' to choose whether to engage with these apps. To some, it might seem ambitious to attribute so much blame to digital nudges, especially when people have autonomy and can simply log out or delete the app.

However, the issue here is that nudges rely on non-rational elements of consciousness, making it quite difficult to tell when one is being nudged. Additionally, there is intention here: nudges are designed to make these apps addictive. For instance, in the article “Has Technology Become Addictive?”, Adam Alter argues 'the people who create and refine tech...run thousands of tests with millions of users to learn which tweaks work and which ones don't....as an experience evolves, it becomes an irresistible, weaponised version of the experience it once was.' As such, it is clear that "logging off" is not as straightforward for users because the environment is intentionally designed to make disengagement challenging.

Another big issue with this form of digital nudging is that it is ultimately exploitative. Exploitation can be defined as “the act of using someone or something unfairly for your advantage.” Traditional analogue nudges are usually justified from a paternalistic lens, a way for the government to help citizens “for their own good”. For example, through manipulating choice environments to make individuals stop smoking or eat more fruit, whilst this might interfere with one’s autonomy, it is justified (to some) because it is not ill-intentioned and it often encourages seemingly “good” behaviour. This? infinite scrolling? automatic refreshing? likes? It’s all for corporate profit, and it’s harmful.

Additionally, using these nudges during particularly vulnerable periods, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, when external factors made it easier to erode natural stopping cues was even more exploitative. This is because it was a period where, arguably, there should have been a heightened responsibility among technologists to advocate for healthier usage patterns, especially if one takes into consideration the growing reliance on their apps for social connection. However, this responsibility was not considered, as digital nudges were employed to continue to drive users towards prolonged social media engagement.

There’s another argument that I will consider to not seem like the social media grinch (I promise, I’m not!) This argument is that there is a clear “business of social media" which may benefit us all. From this lens, nudging may seem like an inherent problem; it may be viewed as simply enhancing the functionality and profitability of social media and networking apps. The persuasive psychological techniques employed by digital nudges make the apps more engaging, which ultimately increases their profitability. This argument holds some strength when we consider the benefits of being online and connected. For example, the learning opportunities, increased global connectivity, and the economic benefits of a creator economy. From a business standpoint, increased profitability is typically advantageous for shareholders, creators themselves and may be viewed as having a knock-on impact on society in that it could incentivise greater creativity. With this in mind, proponents could argue that using digital nudging is ultimately not entirely problematic and might actually be positive. As a result, some may conclude that social media platforms offer numerous benefits and profitability that incentivise innovation and social connection and that it ultimately falls upon users to decide how to navigate their social media usage.

However, the strength of this argument, in my opinion, is questionable at best. It does not absolve digital nudges against the claim that they are problematic. This is because problematic digital nudges are unnecessary in achieving this aim of engagement with apps and the profitability of apps. There is room for responsible innovation. For instance, Tristan Harris notes that there are alternative forms of nudges that can be used to nudge users in a way that benefits them online, such as 'convert(ing) intermittent variable rewards into less addictive, more predictable ones with better design’.

Image credits: Social Dilenma, Netflix

Ultimately, if you find yourself constantly scrolling, I hope this article has explained at least to an extent why and also made you realise just how problematic that is. There’s still much more that can be explored; another thing I’m really interested in is the use of social media as a pacifier and what this has done for our society. Maybe I’ll discuss this another day.

If you’re interested in this topic and want to read more, then here are some recommendations:

(2021) Pathways: How digital design puts children at risk. Available at: https://5rightsfoundation.com/uploads/Pathways-how-digital-design-puts-children-at-risk.pdf

Bhargava, V. R. & Velasquez, M. (2021) Ethics of the Attention Economy: The Problem of Social Media Addiction. Business ethics quarterly. [Online] 31 (3), P.321.

Harris, T. (2019) How technology is hijacking your mind - from a former insider, Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/thrive-global/how-technology-hijacks-peoples-minds-from-a-magician-and-google-s-design-ethicist-56d62ef5edf3

Smith, J. & de Villiers-Botha, T. (2023) Hey, Google, leave those kids alone: Against hypernudging children in the age of big data. AI & society. [Online] 38 (4), 1639–1649.

The Social Dilemma Documentary, Netflix, 2020

Véliz, C. (ed.) (2021) The Oxford handbook of digital ethics. [Online]. Oxford: Oxford University Press. P.357

This was amazing and very eye opening, I also struggled with doom scrolling and thought it was a self discipline issue but after reading this article it shows me that it is more than that and maybe I should give myself more grace when trying to overcome the issue of doom scrolling. I also found your point of digital nudging very interesting I did not know that was a thing.